- Received On: 2021-11-26|

- Accepted On: 2022-02-20|

- Published On: 2022-03-16

| Article Metadata | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Submitted Manuscript | PPD/MIN/2111/1 | |

| 2 | Cover Letter to Editor | PPD/CLE/2111/1 | |

| 3 | Copyright Transfer Letter | PPD/CTL/2111/1 | |

| 4 | Authors’ Consent Letter | PPD/ACL/2111/1 | |

| 5 | Initial Editorial Screening Report | PPD/IESR/2111/1 | |

| 6 | Review Agreement Letter (Reviewer 1) | PPD/RAL/21111/R1 | |

| 7 | Review Agreement Letter (Reviewer 2) | PPD/RAL/21111/R2 | |

| 8 | Manuscript Review Report (Round 1, Reviewer 1) | PPD/MRR/21111/R1.1 | |

| 9 | Manuscript Review Report (Round 1, Reviewer 2) | PPD/MRR/21111/R1.2 | |

| 10 | Revised Manuscript | PPD/MIN/21111R | |

| 11 | Review Response Letter (Round 1) | PPD/RRL/21111/R1 | |

| 12 | Manuscript Review Report (Round 2, Reviewer 1) | PPD/MRR/21111/R2.1 | |

| 13 | Manuscript Review Report (Round 2, Reviewer 2) | PPD/MRR/21111/R2.2 | |

| 14 | Final Editorial Screening Report | PPD/FESR/21111 | |

| 15 | Letter of Acceptance and Acknowledgement | PPD/LAA/21111 | |

| 16 | Accepted Manuscript | PPD/MIN/21111A | |

| Request Access | |||

| Supplementary Data | ||

|---|---|---|

| The datasets used and/or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. | ||

| Datasets | Not Provided | Request Availability |

Abstract

Medicinal plants are the primary sources of easily accessible remedies frequently used by the traditional people in developing regions. It is a common practice for sick people to combine conventional medicine with traditional medicine. Clove and Tulsi are among the most widely used herbs prescribed for their therapeutic benefits in a wide range of ailments. The purpose of this review was to accumulate and compare the benefits of both plants by focusing on their phytochemical and nutraceutical components and biological responses. Ethnomedicinal data were obtained through extracting information from journals, books, and websites belonging to the therapy. The study categorized the pharmacological properties possessed by these two plants according to their bioactive compounds, among which eugenol was found most potent and commonly present in both offering antioxidant, and anesthetic activities. Other common phytochemical components of essential oils include α-Pinene, β-Pinene, Limonene, and Camphene, 1.8-Cineole, α-Terpineol, β-Caryophyllene, Germacrene D, δ-Cadinene, α-Selinene, α-Cadinol, etc. In literature, both these plants have been reported to have a wide variety of pharmacological potentials including antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, chemopreventive, radioprotective, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, anthelmintic, anticoagulant activities. The study also identified some key areas as opportunities for further scientific investigations such as assessment of safety profile of co-administration, alternative use, nutraceutical values, and disease-specific dose determination, etc. The study compiled comparative information to aid scientists for additional research and the tribal communities for specifying targeted use against particular diseases.

Introduction

Natural plants have long been used as medicinal agents due to their biological and pharmacological activities since ancient times. Different parts of plants and their crude extracts have been employed for centuries in herbal medicine to prevent diseases, both therapeutically and prophylactically. Clove and Tulsi are known for their ethnomedicinal values and are considered abundant sources of bioactive compounds. Different compounds and plant parts of these herbs have been found to ameliorate various clinical conditions.

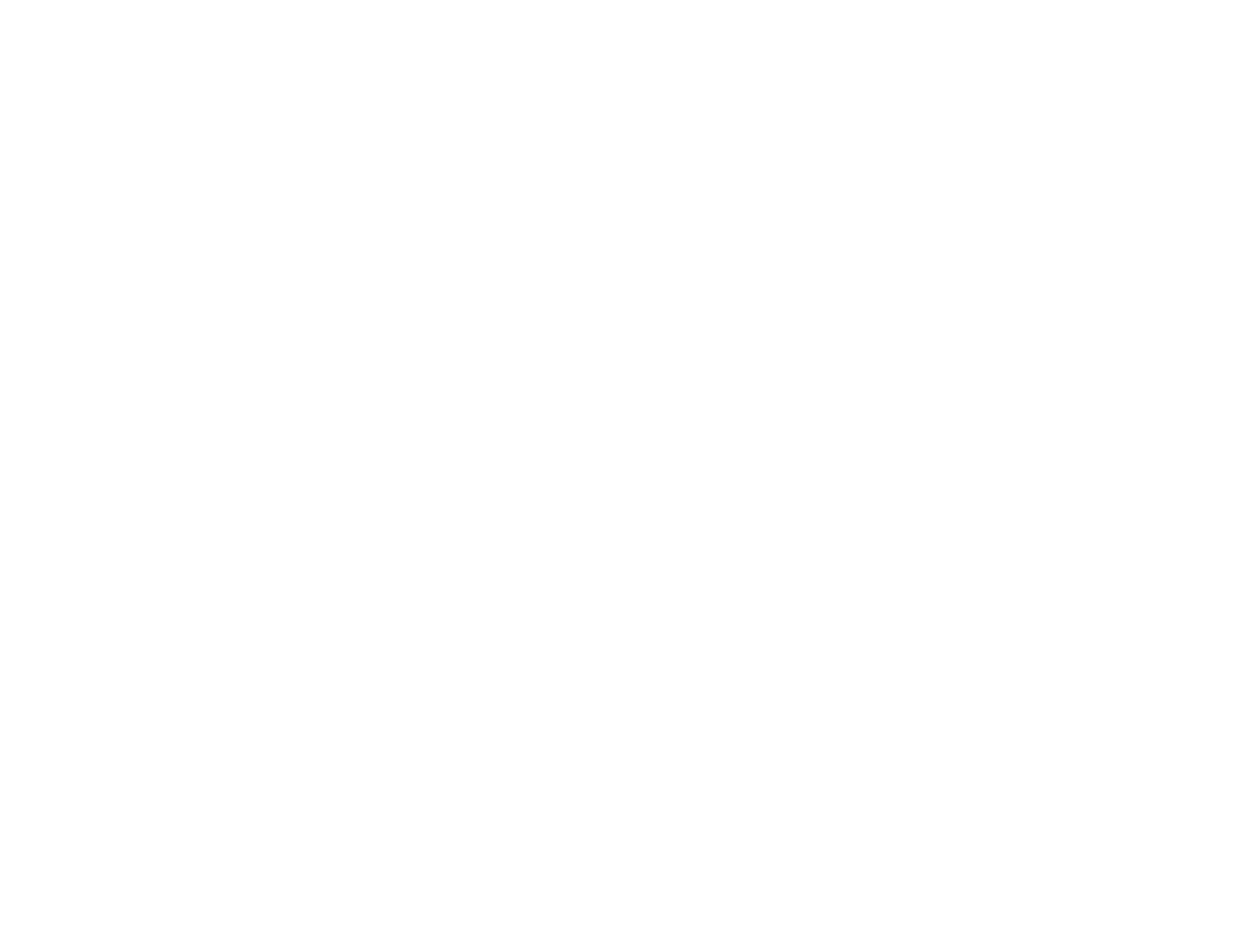

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) is an aromatic plant, belonging to Myrtaceae family (Table 1). It is indigenous to the Maluku Islands, off the coast of east Indonesia. However, it is currently grown in Sri Lanka, India, Madagascar, Malaysia, Tanzania (Zanzibar Island) and in the northeast regions of Brazil [1]. The whole and ground cloves are used to enhance the flavor of dishes. They are utilized as a carminative to promote peristalsis and enhance gastric hydrochloric acid [2]. It has been proven to be a good anesthetic for sedating fish in a variety of invasive and noninvasive fisheries management and research techniques [3]. Furthermore, clove essential oil possesses a wide range of biological activities, including antibacterial, antioxidant, antifungal, antiseptic, and insecticidal effects [4-6]. The abundance of eugenol, a highly potent pharmacologically active compound, in clove essential oil is responsible for most of the biological activities however, other compounds are still in research.

Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum L.) is an aromatic shrub belonging to the Lamiaceae family of basil (tribe ocimeae). It originated in north-central India and is now cultivated as a native species in the eastern tropics of the world [7]. Tulsi is one of the most well-known examples of Ayurveda's holistic approach to healthcare. Tulsi has been included in spiritual and lifestyle practices in India, which is due to its wide range of health benefits. Several types of research have been conducted based on traditional Ayurvedic wisdom to investigate the medicinal benefits of tulsi and have suggested that this herb is a tonic for the body, mind, and spirit that can treat a variety of modern-day health issues. Tulsi is said to improve the appearance of the skin, the sweetness of the voice, and the development of intelligence, and stamina [8,9]. Leaves, fruits, essential oils of tulsi exert anti-tussive, antioxidant, antimicrobial, radioprotective, antihypertensive, and immunomodulatory effects [10-14].

This review mainly focused on the comparative study of Syzygium aromaticum (Clove) and Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) depending on their nutraceutical values, compositions, essential oils, traditional applications, biological and toxic effects in order to have a clear concept of the similarities and dissimilarities between the two medicinal plants.

Table 1: Taxonomical classification of S. aromaticum and O. sanctum [15,16]

Ethnomedicinal Use

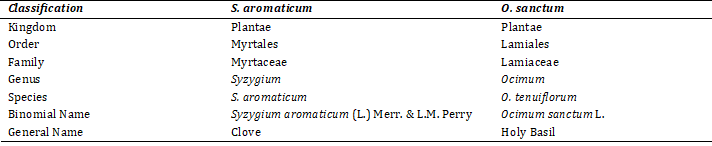

Syzygium aromaticum (clove) and Ocimum sanctum (tulsi) have been documented as the most prominent sources of traditional medicine for centuries. Approximately 80% of the world's population currently depends on traditional medicines as a primary source of health treatment [17]. Different parts of these plants are traditionally used in Ayurveda and Siddha medicine to prevent and treat a variety of illnesses and everyday ailments which have been shown in Table 2. Within Ayurveda practice, tulsi is renowned as “The Queen of Herbs,” “Mother Medicine of Nature” and is revered as an “elixir of life”. It is said that daily consumption of tulsi prevents disease, promotes general health, wellbeing, and further helps to manage the stresses of daily life. Chewing leaves helps to treat cold and sore throat [18]. In ancient times, the leaves are used to treat a variety of fevers such as boiled leaves are taken with tea as a treatment to prevent dengue and malaria fever whereas dried powder of leaf is used to cure teeth disorder [19]. On the other hand, cloves have traditionally been used as a remedy for indigestion, nausea, and vomiting. Cloves have been used to cure a variety of illnesses including malaria, cholera, and tuberculosis in tropical Asia. In America, it's used to treat different types of worms and viruses, candida, and a number of protozoan and bacterial infections. In addition to their recreational purposes, cloves are said to be a natural anthelmintic [20].

Table 2: Comparison of ethnomedicinal uses between S. aromaticum and O. sanctum plant parts

Alongside, these two are popular as condiments and flavoring agents in preparing traditional dishes as well as common ingredients in formulating toothpaste commercially [79,80].

Nutraceutical Compounds

The composition of a clove varies slightly as it is produced, processed, and stored in the agro-climatic conditions. A typical evaluation determines the following approximate chemical composition of clove: volatile oil (13.2%), non-volatile ether (15.5%), carbohydrate (57.7%), protein (6.3%), crude fibre (11.1%), mineral matter (5.0%), calcium (0.7%), phosphorus (0.11%), iron (0.01%), sodium (0.25%), potassium (1.2%), ash insoluble in HCl (0.24%), vitamins (mg/100g): Vit A: 175 I. U., Vit B1: 0.11, Vit B2: 0.04, niacin:1.55, Vit C:80.9 and calorific value (food energy): 430 calories/100g [20]. The nutritional analysis of Ocimum sanctum exhibits a high level of protein (30 Kcal, 4.2 g), carbohydrate (2.3 g), and fat (0.5 g) contents. It also contains vitamin A and C (25 mg per 100 g), and minerals such as calcium (25 mg), iron (15.1 mg), and phosphorus (287 mg) [9].

Phytochemical Constitutes

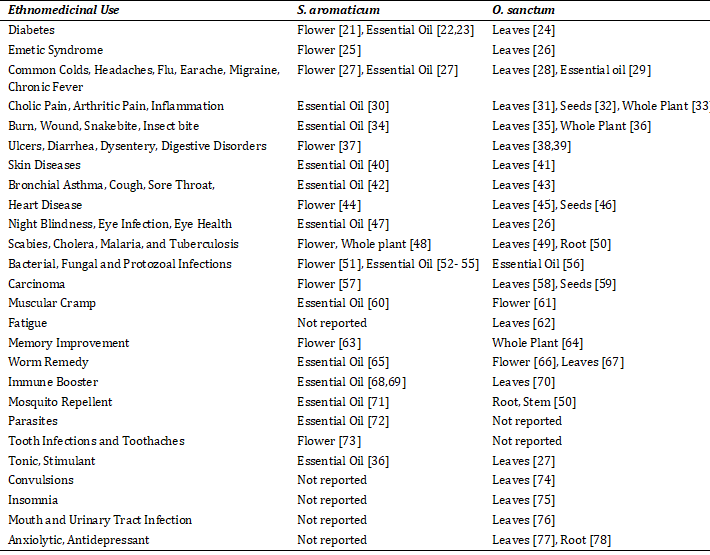

The nature of compounds present in medicinal herbs can be identified through phytochemical analysis. It is also performed to evaluate the effects of available bioactive components. Phytochemical constituents such as eugenol, polyphenols, flavonoids have been considered to be a valuable source for the development of innovative pharmaceutical compounds that have been utilized to treat serious ailments [81]. Clove and tulsi possess a wide range of phytocompounds that have been compared in Table 3. Among them, the content of eugenol is found to be the most common in both these plants apart from other mutual compounds such as gallic acid, oleanolic acid, stigmasterol, campesterol, etc. Besides, these medicinal plants also contain bicyclic sesquiterpenes, phenolic compounds, phenolic acids, triterpenes, C-glucosides, flavonoids, tannins, triterpenoid saponins, and steroids which have been demonstrated to have pharmacological actions.

Table 3: Comparison of phytochemical compounds of whole plants of S. aromaticum and O. sanctum.

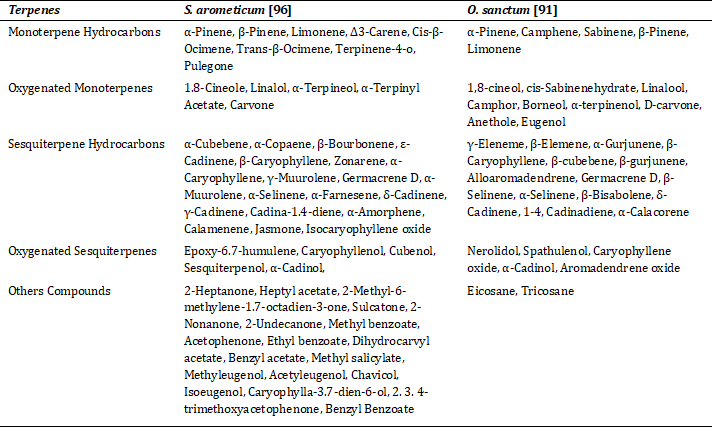

Phytochemical Constitutes of Essential Oil

Terpenes, or terpenoids, are the most abundant and diversified class of naturally occurring chemicals in natural plants. They are categorized as mono, di, tri, tetra, as well as sesquiterpenes depending on the number of isoprene units they contain. Table 4 categorizes monoterpene, oxygenated monoterpenes, sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, oxygenated sesquiterpenes and other compounds present in clove and tulsi. Among monoterpene hydrocarbons, both plants are enriched with α-Pinene, β-Pinene, Limonene, and Camphene. Besides, some compounds such as 1.8-Cineole, α-Terpineol, β-Caryophyllene, Germacrene D, δ-Cadinene, α-Selinene, α-Cadinol contained by sesquiterpenes are the most common in these two natural herbs [91,96].

Table 4: Comparison of phytochemical constitutes of essential oils of S. aromaticum and O. sanctum.

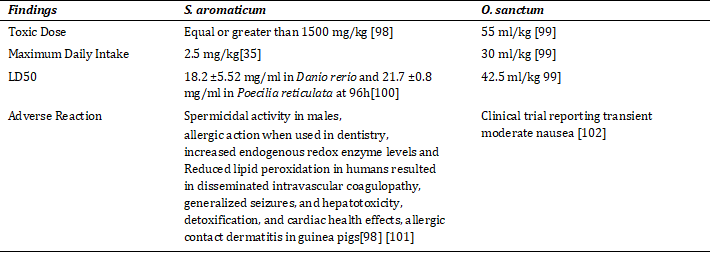

Toxicological Studies

Many studies have reported several therapeutic actions of S. aromaticum and O. sanctum. The World Health Organization (WHO) found that the daily amount of clove that is acceptable in humans is 2.5 mg/kg of weight whereas the daily consumption of tulsi is 30 ml/kg (Table 5). It can cause possible side effects such as liver damage, seizures, and fluid imbalances. There have not been found noteworthy evidences about clove's safety in medicinal doses [97]. However, it has been recommended to avoid its use for pregnant or breastfeeding women [97]. In respect of tulsi, studies revealed favorable therapeutic results with low or no side effects for formulations, irrespective of dose, or for any participant's age or gender [28].

Table 5: Toxic Dose and Safety profile of S. aromaticum and O. sanctum.

The absence of any adverse effects does not rule out the possibility of long-term side effects. However, the long traditional history of daily usage of tulsi indicating any major long-term health risks are rare and daily intake of tulsi has been reported safe [28].

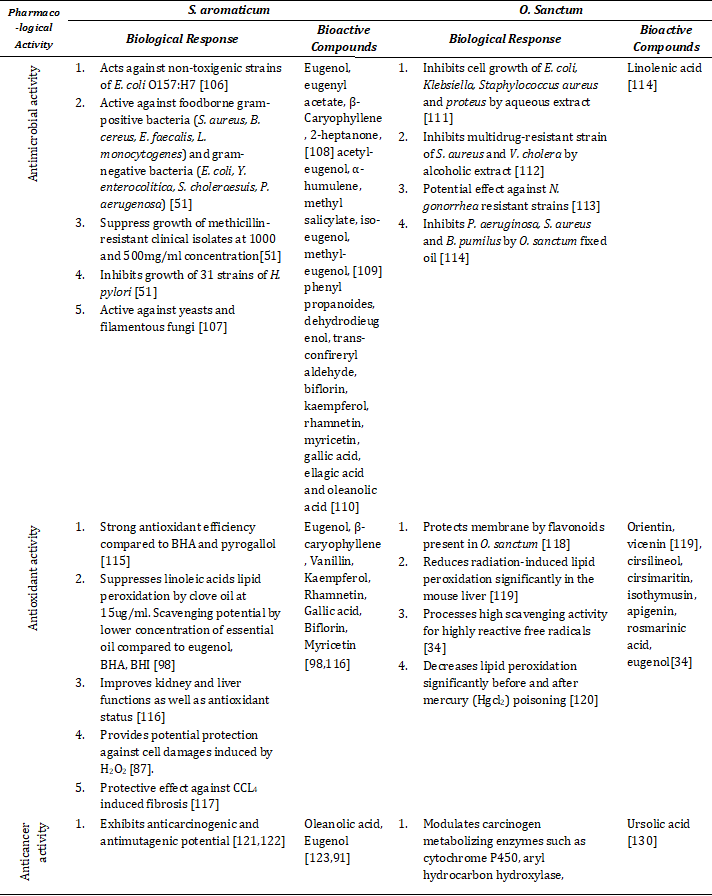

Biological Responses

Clove and Tulsi are essential therapeutic plants because of the extensive spectrum of pharmacological properties accumulated over centuries of traditional use and documented in literatures. These plants are abundant with many phytoconstitutes that leads many researchers to identify specific compounds in response to particular disease. Eugenol, the major compound of clove is reported to participate in photochemical reactions [103]and photocytotoxic properties [104]. In 1995, the radioprotective effect of Ocimum sanctum was first documented [105]. Besides, clove and tulsi both plants have showed antibacterial, antifungal, anticarcinogenic, analgesic, cardioprotective, anti- inflammatory, anti-fertility activities depending on their phytoconstituents. Table 6 represents biological responses of both plants according to their phytocompounds.

Table 6: Comparative summary of pharmacological properties of S. aromaticum and O. sanctum by representing the biological responses and responsible bioactive compounds.

Recommendations

The review recommends a wide range of pharmaceutical activities categorized based on their bioactive compounds. However, it also identified opportunities for further investigations in vital areas. As such, no studies were found on the co-administration (intake) of these two plants in laboratory or human model to identify their safety profile, adverse reactions or contraindications whereas, in vice versa, no report suggested their use in ailments alternatively. Moreover, very few studies documented the nutrients presents in isolated parts of these herbs. In addition, no studies were found on determining the daily intake or safe doses individually for particular diseases or disorder. Thus, current comparison recommends further phytochemical and pharmacological analysis to establish clove and tulsi as prescribed natural agents.

Conclusion

The role of natural plants in medicine have always been well-documented in literatures. This review was focused on the comparison of traditional uses, biological responses, chemical compositions, toxicity and safety profiles of clove and tulsi herbs. Alongside the comparative analysis, the study also revealed common constituents and common pharmacological activities among these two plants; which have indicated the role of different bioactive compounds for same biological responses. The review concludes that both clove and tulsi are highly potent pharmacological agents and can be used for different ailments prior assessing their safe dose profile against the particular disease or disorder.

Acknowledgements

The present study was mapped and structured at the Institute for Pharmaceutical Skill Development and Research, Bangladesh.

Authors’ Contributions

Authors MNI structured and organized the project. Author JS collected the findings and prepared the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

Authors agreed on the article before submission and had no conflict of interests.

References

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): A precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4(2):90-96. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Nassan M, Mohamed E, Abdelhafez S, Ismail T. Effect of clove and cinnamon extracts on experimental model of acute hematogenous pyelonephritis in albino rats: Immunopathological and antimicrobial study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2015;28(1):60-68. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Prince A, Powell C. Clove oil as an anesthetic for invasive field procedures on adult rainbow trout. North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 2000;20(4):1029-1032. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Lee KG, Shibamoto T. Antioxidant property of aroma extract isolated from clove buds [Syzygium aromaticum (L.)Merr. et Perry]. Food Chemistry. 2001;74(4):443-448. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Núñez L, D’Aquino M, Chirife J. Antifungal properties of clove oil (Eugenia caryophylata) in sugar solution. Braz J Microbiol. 2001; 32:123-126. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Zainol SN, Said SM, Abidin ZZ, Azizan N, Majid F a. A, Jantan I. Synergistic benefit of Eugenia Caryophyllata L. and Cinnamomum Zeylanicum Blume essential oils against oral pathogenic bacteria. Chemical Engineering Transactions. 2017;56:1429-1434. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Bast F, Rani P, Meena D. Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of Holy Basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum) in Indian subcontinent. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014: e847482. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Mohan L, Amberkar MV, Kumari M. Ocimum sanctum Linn (Tulsi) - an overview. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research. 2011;7(1):51-53. Link

- Pattanayak P, Behera P, Das D, Panda SK. Ocimum sanctum Linn. A reservoir plant for therapeutic applications: an overview. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4(7):95-105. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar

- Mondal S, Mirdha BR, Mahapatra SC. The science behind sacredness of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn.).Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;53(4):291-306. PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Tiwari M, Murugan R, Tulsawani R, et al. Factors affecting radioprotective efficacy of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) extract in mice. JAMPS. 2016;9(9):1-12. DOI Link

- Mondal S, Varma S, Bamola VD, et al. Double-blinded randomized controlled trial for immunomodulatory effects of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) Leaf extracton healthy volunteers. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(3):452-456. DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Meghwani H, Prabhakar P, Mohammed SA, et al. Beneficial effect of Ocimum sanctum (Linn) against monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5(2):34. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Deore SL, Jaju PS, Baviskar BA. Simultaneous estimation of four antitussive components from herbal cough syrup by HPTLC. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014; 2014:1-7. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System - Report (ITIS): Syzygium aromaticum. Accessed February 11, 2022. Link

- Dash BK, Azam M, Or-Rashid A, Hafiz F, Sen M. Ethnomedicobotanical study on Ocimum sanctum L. (Tulsi) -A review. Mintage Journal of Pharmaceutical & Medical Sciences. 2013; 2. Google Scholar Link

- Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014;4(177):1-7. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- 7 health benefits of Tulsiplant. Care Health Insurance. Updated February 01, 2022. Accessed February 11, 2022. Link

- M. S, Shanmugam KR, Bhasha DS, G. V. Ocimum sanctum: A review on the pharmacological properties. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 2016;5(3):558-565. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Bhowmik D, Kumar K, Yadav A, Paswan S. Recent trends in Indian traditional herbs Syzygium aromaticum and its health benefits. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2012; 1 (1):13-23. Google Scholar Link

- Kuroda, M., Mimaki, Y., Ohtomo, T., Yamada, J., Nishiyama, T., Mae, T., Kishida, H., & Kawada, T. Hypoglycemic effects of clove (Syzygium aromaticum flower buds) on genetically diabetic KK-Ay miceand identificationof the active ingredients. Journal of Natural Medicines.2012;66(2):394–399. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Tahir HU, Sarfraz RA, Ashraf A, Adil S. Chemical composition and antidiabetic activity of essential oils obtained from two spices (Syzygium aromaticum and Cuminum cyminum). International Journal of Food Properties. 2016;19(10):2156-2164. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Prasad RC, Herzog B, Boone B, Sims L, Waltner-Law M. An extract of Syzygium aromaticum represses genes encoding hepatic gluconeogenic enzymes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2005;96(1-2):295-301. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Vats V, Grover JK, Rathi SS. Evaluation of anti-hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic effect of Trigonella foenum-graecum Linn, Ocimum sanctum Linn and Pterocarpus marsupium Linn in normal and alloxanized diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;79(1):95-100. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh J, Baghotia A, SP G. Eugenia caryophyllata Thunberg (Family Myrtaceae): A Review. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2012;3(4):1469–1475. Google Scholar Link

- Sethi L, Bhadra P. A review paper on Tulsi plant (Ocimum sanctum L.). Indian Journal of Natural Sciences. 2020; 10(60):20854-20860.

- Vicidomini C, Roviello V, & Roviello GN. Molecular basis of the therapeutical potential of clove (Syzygium aromaticum L.) and clues to its anti-COVID-19 utility. Molecules. 2021;26(7):1880. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Jamshidi N, Cohen MM. The clinical efficacy and safety of Tulsi in humans: A systematic review of the literature. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.2017; 2017:1-13. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Ahmadifard M, Yarahmadi S, Ardalan A, Ebrahimzadeh F, Bahrami P, Sheikhi E. The efficacy of topical basil essential oil on relieving migraine headaches: A randomized triple-blind study.Complement Med Res. 2020;27(5):310-318. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Grespan R, Paludo M, Lemos H de P, et al. Anti-arthritic effect of eugenol on collagen-induced arthritis experimental model. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2012;35(10):1818-1820. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Komeh-Nkrumah SA, Nanjundaiah SM, Rajaiah R, Yu H, Moudgil KD. Topical dermal application of essential oils attenuates the severity of adjuvant arthritis in Lewis rats: Antiarthritic activity of essential oils. Phytother Res. 2012;26(1):54-59. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Mirje MM, Zaman SU, Ramabhimaiah S. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn (Tulsi) in Albino rats. 2014;3(1):198-205. Google Scholar Link

- Calderón Bravo H, Vera Céspedes N, Zura-Bravo L, Muñoz LA. Basil seeds as a novel food, source of nutrients and functional ingredients with beneficial properties: A review. Foods. 2021;10(7):1467. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Kelm MA, Nair MG, Strasburg GM, DeWitt DL. Antioxidant and cyclooxygenase inhibitory phenolic compounds from Ocimum sanctum Linn. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(1):7-13. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- El-Saber Batiha G, Alkazmi LM, Wasef LG, Beshbishy AM, Nadwa EH, Rashwan EK. Syzygium aromaticum L. (Myrtaceae): Traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents, pharmacological and toxicological activities. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2):202. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Kumar KS, Bhowmik D,Biswajit, et al. Traditional Indian herbal plants Tulsi and its medicinal importance.Research Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry.2010;2(2):93-101. Google Scholar Link

- Leung AY, Khan IA, Abourashed EA . Leung’s Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients Used in Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics. A John Wiley & Sons, Cop; 2010. Google Scholar Link

- Dharmani P, Kuchibhotla VK, Maurya R, Srivastava S, Sharma S, Palit G. Evaluation of anti-ulcerogenic and ulcer- healingproperties of Ocimum sanctum Linn. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;93(2-3):197-206. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Vaseem A, Ali M, Afshan K. Activity of Tulsileaves(Ocimum sanctum linn) in protecting gastric ulcer in ratsbycold restrains method. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 2017;6(10):2343-2347. DOI Link

- Fu Y, Chen L, Zu Y, et al.The antibacterial activity of clove essential oil against propionibacterium acnes and its mechanism of action. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(1):86-88. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Mohammadi Nejad S, Özgüneş H, Başaran N. Pharmacological and toxicological properties of eugenol. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2017;14(2):201-206. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Aisha AFA, Abu-Salah KM, Alrokayan SA, Siddiqui MJ, Ismail Z, Majid AMSA. Syzygium aromaticum extracts as good source of betulinic acid and potential anti-breast cancer.Rev bras farmacogn. 2012;22(2):335-343. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Rai V, Iyer U, Mani UV. Effect of Tulasi (Ocimum sanctum) leaf powder supplementation on blood sugar levels, serum lipids and tissues lipids in diabetic rats. Plant Food Hum Nutr. 1997;50(1):9-16. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Chegu K, Mounika K, Rajeswari M, et al. In vitro study of the anticoagulant activity of some plant extracts. World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2019;7: 904-913. Link

- Suanarunsawat T, Boonnak T, Ayutthaya WDN, Thirawarapan S. Anti-hyperlipidemic and cardioprotective effects of Ocimum sanctum L.fixed oil in rats fed a high fat diet. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. 2010;21(4):387-400. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Rehan HMS, Majumdar DK. Effect of Ocimum sanctum fixed oil on blood pressure, blood clotting time and pentobarbitone-induced sleeping time. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2001;78(2-3):139-143. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Mohamed M, Abdallah A, Mahran M, Shalaby A. Potential alternative treatment ofocular bacterial infections by oil derived from Syzygium aromaticum flower (Clove). Current Eye Research. 2018;43(7):873-881. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- DeFilipps RA,Krupnick GA. The medicinal plants of Myanmar. PhytoKeys. 2018;(102):1-341. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Inbaneson SJ, Sundaram R, Suganthi P. In vitro antiplasmodial effect of ethanolic extracts of traditional medicinal plant Ocimum species against Plasmodium falciparum. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2012;5(2):103-106. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Patel RR. Tulsi: The queen of medicinal herbs.Journal of Bioequivalence & Bioavailability.2020;12(6):407. Link

- Mounika AM, Sushma MS, Sidde L, Malathi S, Rajani K. Invitro evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Clove buds (Euginea aromatica).International Journal of Indigenous Herbs and Drugs. 2020;5(4):25-33. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Chee HY, Lee MH. Antifungal activity of Cloveessential oil and its volatile vapouragainstdermatophytic fungi. Mycobiology. 2007;35(4):241-243. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Schmidt E, Jirovetz L, Wlcek K, et al. Antifungal activity of eugenol and various eugenol-containing essential oils against 38 clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants. 2007;10(5):421-429. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Xu JG, Liu T, Hu QP, Cao XM. Chemical composition, antibacterial properties and mechanism of action of essential oil from Clovebuds against Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules. 2016;21(9):1194. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Kalemba D, Kunicka A. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of essential oils. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;10(10):813-829. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Amber K, Aijaz A, Immaculata X, Luqman KA, Nikhat M. Anticandidal effect of Ocimum sanctumessential oil and its synergy with fluconazole and ketoconazole. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(12):921-925. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Banerjee S, Panda CKr, Das S. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum L.), a potential chemopreventive agent for lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(8):1645-1654. DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Bhattacharyya P, Bishayee A. Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Tulsi): An ethnomedicinal plant for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2013;24(7):659-666. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Prakash J, Gupta SK. Chemopreventiveactivity of Ocimum sanctum seed oil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;72(1-2):29-34. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Parle M, Khanna D. Clove: A champion spice. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy. 2010;2(1):47-54. Link

- Kaur G, Jaggi AS, Singh N. Exploring the potential effect of Ocimum sanctum in vincristine-induced neuropathic pain in rats. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2010; 5:3. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Kassab R, Bauomy A. The neuroprotective efficency of the aqueous extract of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) in aluninium-induced neurotoxicity. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014; 6:503-508. Link

- Halder S, Mehta AK, Kar R, Mustafa M, Mediratta PK, Sharma KK. Cloveoil reverses learning and memory deficits in scopolamine-treated mice. Planta Med. 2011;77(8):830-834. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Giridharan VV, Thandavarayan RA, Konishi T. Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Holy Basil) to improve cognition. Diet and Nutrition in Dementia and Cognitive Decline.2015:1049-1058. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Pant A, Prakash P, Pandey R, Kumar R. Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Elicits lifespan extension and attenuates age-related Aβ-induced proteotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cogent Biology. 2016;2(1):1218412. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Anees AM. Larvicidal activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Labiatae) against Aedes aegypti (L.) and Culex quinquefasciatus (Say). Parasitol Res. 2008;103(6):1451-1453. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Buchineni M, Pathapati RM, Kandati J, Buchineni M. Anthelmintic activity of tulsi leaves (Ocimum Sanctum Linn)-An in-vitro comparative study.Saudi Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences.2015;1(2):47-49. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Dibazar SP, Fateh S, Daneshmandi S. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) ingredients affect lymphocyte subtypes expansion and cytokine profile responses: An in vitro evaluation. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2014;22(4):448-454. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Han X, Parker TL. Anti-inflammatory activity of clove (Eugenia caryophyllata) essential oil in human dermal fibroblasts. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2017;55(1):1619-1622. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Das R, Raman RP, Saha H, Singh R. Effect of Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Tulsi) extract on the immunity and survival of Labeorohita (Hamilton) infected with Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquac Res. 2015;46(5):1111-1121. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Barnard DR. Repellency of essential oils to mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1999;36(5):625-629. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Yang YC, Lee HS, Clark JM, Ahn YJ. Insecticidal activity of plant essential oils againstPediculus humanus capitis (Anoplura: Pediculidae). J Med Entomol. 2004;41(4):699-704. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Kothiwale SV, Patwardhan V, Gandhi M, Sohoni R, Kumar A. A comparative study of antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of herbal mouth rinse containing tea tree oil, clove, and basil with commercially available essential oil mouth rinse. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18(3):316-320. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar

- Jaggi R, Madaan R, Singh B. Anticonvulsant potentialof Holy Basil, Ocimum sanctumLinnand its cultures. Indian journal of experimental biology. 2003;41:1329-1333. PubMed Google Scholar Link

- N BA, Ghosh, AR, M, CH, S, NH, R, PB, Dr. Krishna KL. Review on nutritional, medicinal and cns activities of tulsi (Ocimum. sanctum). Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2020;12(3):420-426. Google Scholar Link

- Ali H, Dixit S. in vitro antimicrobial activity of flavanoids of Ocimum sanctum with synergistic effect of their combined form. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2012; 2(1):S396-S398. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Chatterjee M, Verma P, Maurya R, Palit G. Evaluation of ethanol leaf extract of Ocimum sanctum in experimental models of anxiety and depression. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2011;49(5):477-483. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Dhingra D, Sharma A. A review on antidepressant plants. Indian Journal of Natural Products and Resources. 2006; 5(2):144-152. Link

- Wilson L. Spices and Flavoring Crops: Leaf and Floral Structures. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. 2016; 9 : 84-92. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-384947-2.00780-7 Google Scholar Link

- Pal RS, Pal Y, Saraswat N, Wal P. A review on the recent flavoring herbal medicines of today. Open Medicine Journal. 2020;7(1):1-6. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Lahlou M. The Success of natural products in drug discovery. Pharmacology & Pharmacy.2013; 4:17-31. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Anandjiwala S, Kalola J, Rajani M. Quantification of eugenol, luteolin, ursolic acid, and oleanolic acid in black (Krishna Tulasi) and green (Sri Tulasi)varieties of Ocimumsanctum Linn. using high-performance thin-layer chromatography. Journal of Aoac International. 2006;89(6):1467-1474. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Jirovetz L, Buchbauer G, Stoilova I, Stoyanova A, Krastanov A, Schmidt E. Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of clove leaf essential oil. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(17):6303-6307. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Upadhyay R. Tulsi: A holy plant with high medicinal and therapeutic value. International Journal of Green Pharmacy. 2017; 11:S1-S12. Google Scholar Link

- Sundaram RS, Ramanathan M, Rajesh R, Satheesh B, Saravanan D. Lc-Ms quantification of rosmarinic acid and ursolic acid in the Ocimum Sanctum Linn. leaf extract (holy basil, tulsi). Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies. 2012;35(5):634-650. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Ladurner A, Zehl M, Grienke U, et al. Allspice and clove as source of triterpene acids activating the g protein-coupled bile acid receptor TGR5. Front Pharmacol. 2017; 8: 1-13. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Mittal M, Gupta N, Parashar P, Mehra V, Khatri M. Phytochemical evaluation and pharmacological activity of Syzygium aromaticum: a comprehensive review. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.2014:6(8):67-72. Google Scholar Link

- Lam KY, Ling APK, Koh RY, Wong YP, Say YH. A review on medicinal properties of orientin. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2016; 2016:1-9. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Pandey G, Sharma M. Pharmacological activities of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi): A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research. 2010; 5: 61-66. Google Scholar Link

- Shan B, Cai YZ, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant capacity of 26 spice extracts and characterization of their phenolic constituents.J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(20):7749-7759. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Hussain AI, Chatha SAS, Kamal GM, Ali MA, Hanif MA, Lazhari MI. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oil and extracts from Ocimum sanctum. International Journal of Food Properties. 2017;20(7):1569-1581. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Chaula D, Laswai H, Chove B, et al. Effect of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and Seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) water extracts pretreatment on lipid oxidation in sun-dried sardines (Rastrineobola argentea) from Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7(4):1406-1416. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Bao L, Eerdunbayaer E, Nozaki A, et al. Hydrolysable tannins isolated from Syzygium aromaticum: Structure of a new C-glucosidic ellagitannin and spectral features of tannins with a tergalloyl group. ChemInform. 2012; 85(2): 365-381. DOI Google Scholar

- Kadian R, Parle M. Therapeutic potential and phytopharmacology of tulsi. International Journal of Pharmacy & Life Sciences. 2012; 3(7):1858-1867. Google Scholar Link

- Lee HH, Shin JS, Lee WS, Ryu B, Jang DS, Lee KT. Biflorin, isolated from the flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum L.,suppresses LPS-induced inflammatory mediators via STAT1 inactivation in macrophages and protects mice from endotoxin shock. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(4):711-720. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Amelia B, Saepudin E, Cahyana AH, Rahayu DU, Sulistyoningrum AS, Haib J. GC-MS analysis of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) bud essential oil from Java and Manado. Paper presented at:2nd International Symposium on Current Progress in Mathematics and Sciences;November 1-2, 2016:Depok, Jawa Barat, Indonesia. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Bhowmik D, Kumar KPS, Yadav A, Srivastava S, Paswan S, Sankar A. Recent trends in Indian traditional herbs Syzygium aromaticum and its health benefits. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry.2012; 1(1):13-22. Google Scholar Link

- Doleželová P, Mácová S, Plhalová L, Pištěková V, Svobodová Z. The acute toxicity of clove oil to fish Danio Rerio and PoeciliaReticulata. Acta Vet Brno. 2011;80(3):305-308. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Satapathy S, Das N, Bandyopadhyay D, Mahapatra SC, Sahu DS, Meda M. Effect of tulsi(Ocimum sanctum Linn.) supplementation on metabolic parameters and liver enzymes in young overweight and obese subjects. Ind J Clin Biochem. 2017;32(3):357-363. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Mishra RK, Singh SK. Safety assessment of Syzygium aromaticum flower bud (clove) extract with respect to testicular function in mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(10):3333-3338. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Mihara S, Shibamoto T. Photochemical reactions of eugenol and related compounds: Synthesis of new flavor chemicals. J Agric Food Chem. 1982;30(6):1215-1218. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Ogata M, Hoshi M, Urano S, Endo T. Antioxidant activity of eugenol and related monomeric and dimeric compounds. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2000;48(10):1467-1469. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Devi PU, Ganasoundari A. Radio-protectiveeffect of leaf extract of Indian medicinal plantOcimum sanctum. Indian J Exp Biol. 1995;33(3):205-208. PubMed Google Scholar

- Burt SA, Reinders RD. Antibacterial activity of selected plant essential oils against Escherichia Coli O157:H7. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;36(3):162-167. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Pinto E, Vale-Silva L, Cavaleiro C, Salgueiro L. Antifungal activity of the clove essential oil from Syzygium aromaticum on Candida, Aspergillus and Dermatophyte species. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58(11):1454-1462. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Chaieb K, Zmantar T, Ksouri R, et al. Antioxidant properties of the essential oil of Eugenia Caryophyllata and its antifungal activity against a large number of clinical Candidaspecies. Mycoses. 2007;50(5):403-406. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Yang YC, Lee SH, Lee WJ, Choi DH, Ahn YJ. Ovicidal and adulticidal effects of Eugenia caryophyllata bud and leaf oil compounds on Pediculus capitis. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(17):4884-4888. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Cai L, Wu CD. Compounds from Syzygium aromaticum possessing growth inhibitory activity against oral pathogens.J Nat Prod. 1996;59(10):987-990. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Samak G, Vasudevan D, Kedlaya R, Deepa S, Ballal M. Activity of Ocimum sanctum (The traditional Indian medicinal plant) against the enteric pathogens. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2001; 55(8):434-438, 472. PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Aqil F, Khan MSA, Owais M, Ahmad I. Effect of certain bioactive plant extracts on clinical isolates of β-lactamase producing methicillin resistantStaphylococcus aureus. J Basic Microbiol. 2005;45(2):106-114. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Shokeen P, Ray K,Bala M, Tandon V. Preliminary studies on activity of Ocimum sanctum, Drynaria quercifolia, and Annona squamosa against Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(2):106-111. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Malhotra M, Majumdar DK. Antibacterial activity of Ocimum sanctum L. Fixed oil. Indian J Exp Biol; 2005:43(9):835-837. PubMed Google Scholar

- Dorman HJD, Surai P, Deans SG. In vitro antioxidant activity of a number of plant essential oils and phytoconstituents. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 2000;12(2):241-248. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Gülçin İ, Elmastaş M, Aboul-Enein HY. Antioxidant activity of clove oil – A powerful antioxidant source. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2012; 5(4):489-499. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Bakour M, Soulo N, Hammas N, et al. The antioxidant content and protective effect of argan oil and Syzygium aromaticum essential oil in hydrogen peroxide-induced biochemical and histological changes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(2):1-14.610. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Calleja MA, Vieites JM, Montero-Meterdez T, et al. The antioxidant effect of β-caryophyllene protects rat liver from carbon tetrachloride-induced fibrosis by Inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation. Br J Nutr. 2013;109(3):394-401. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Saija A, Scalese M, Lanza M, Marzullo D, Bonina F, Castelli F. Flavonoids as antioxidant agents: Importance of their interaction with biomembranes. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1995;19(4):481-486. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Uma Devi P, Ganasoundari A, Vrinda B, Srinivasan KK, Unnikrishnan MK. Radiation protection by the ocimum flavonoids orientin and vicenin: Mechanisms of action. Radiation Research. 2000;154(4):455-460. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Sharma MK, Kumar M, Kumar A. Protection against mercury-induced renal damage in swiss albino mice by Ocimum sanctum. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2005;19(1):161-167. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Zheng GQ, Kenney PM, Lam LK. Sesquiterpenes from clove(Eugenia caryophyllata) as potential anticarcinogenic agents.J Nat Prod. 1992;55(7):999-1003. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Miyazawa M, Hisama M. Suppression of chemical mutagen-induced sos response by alkyl phenols from clove (Syzygium aromaticum) in the Salmonella typhimurium TA1535/pSK1002 umu test. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49(8):4019-4025. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Liu H, Schmitz JC, Wei J, et al. Cloveextract inhibits tumor growth and promotes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.oncol res. 2014;21(5):247-259. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar

- Ghosh R, Nadiminty N, Fitzpatrick JE, Alworth WL, Slaga TJ, Kumar AP. Eugenol causes melanoma growth suppression through inhibition of e2f1 transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(7):5812-5819. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Banerjee S, Prashar R, Kumar A, Rao AR. Modulatory influence of alcoholic extract of ocimum leaves on carcinogen‐metabolizing enzyme activities and reduced glutathione levels in mouse.Nutrition and Cancer. 1996;25(2):205-217. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Karthikeyan K, Gunasekaran P, Ramamurthy N, Govindasamy S. Anticancer activity ofOcimum sanctum. Pharmaceutical Biology. 1999;37(4):285-290. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Aruna K, Sivaramakrishnan VM. Anticarcinogenic effects of some indian plant products.Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1992;30(11):953-956. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Devi Pu. Radioprotective, anticarcinogenic and antioxidant properties of the Indian holy basil, Ocimum sanctum (Tulasi). Indian J Exp Biol. 2001;39(3):185-90. PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Prashar R, Kumar A, Banerjee S, Rao A. Chemopreventive action by an extract from Ocimum sanctum on mouse skin papillomagenesis and its enhancement of skin glutathione s-transferase activity and acid soluble sulfydryl level: Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1994;5(5):567-572. DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Harsha M, Mohan Kumar KP, Kagathur S, Amberkar VS. Effect of Ocimum sanctum extract on leukemic cell lines: A preliminary in-vitro study. J Oral MaxillofacPathol. 2020;24(1):93-98. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar

- Bhagat N, Chaturvedi A. Spices as an alternative therapy for cancer treatment. SRP. 2016;7(1):46-56. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Sharma M, Pandey G, Sahni Y, Khanna A. Anticancer effect of a herbal drug proimmu on the experimental uterine cancer in rat. Phytomedica. 2010;11:51-58. Google Scholar Link

- Öztürk A, Özbek H. The anti-inflammatory activity of Eugenia caryophyllata essential oil: An animal model of anti-inflammatory activity. Electron J Gen Med. 2005;2(4):159-163. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Kim EH, Kim HK, Ahn YJ. Acaricidal activity of clove bud oil compounds against Dermatophagoides farinae and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Acari: Pyroglyphidae). J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(4):885-889. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Ghelardini C, Galeotti N, Di Cesare Mannelli L, Mazzanti G, Bartolini A. Local anaesthetic activity of beta-caryophyllene. Farmaco. 2001;56(5-7):387-389. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Daniel AN, Sartoretto SM, Schmidt G, Caparroz-Assef SM, Bersani-Amado CA, Cuman RKN. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of eugenol essential oil in experimental animal models.Rev bras farmacogn. 2009; 19: 212-217. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Godhwani S, Godhwani JL, Vyas DS. Ocimum sanctum: An experimental study evaluating its anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activity in animals. J Ethnopharmacol. 1987;21(2):153-163. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Archana R, Namasivayam A. Effect of Ocimum sanctum on noise induced changes in neutrophil functions. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;73(1-2):81-85. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Bawankule D, Kumar A, Agarwal K, et al. Pharmacological and phytochemical evaluation of Ocimum sanctum root extracts for its anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic activities. Phcog Mag. 2015;11(42):217. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Prashar A, Locke IC, Evans CS. Cytotoxicity of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) oil and its major components to human skin cells. Cell Prolif. 2006;39(4):241-248. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Prakash J, Gupta SK. Chemopreventive activity of Ocimum sanctum seed oil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;72(1-2):29-34. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Baliga MS, Jimmy R, Thilakchand KR, et al. Ocimum sanctum L (Holy Basil or Tulsi) and its phytochemicals in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutrition and Cancer. 2013;65Suppl 1:26-35. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Nada AS. Efficacy of clove oil in modulating radiation-induced some biochemical disorders in male rats. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences. 2011; 4(2B):629-647. Google Scholar Link

- Samarth RM, Samarth M, Matsumoto Y. Medicinally important aromatic plants with radioprotective activity. Future Science OA. 2017;3(4):FSO247. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Ganasoundari A, Uma Devi P, Rao BSS. Enhancement of bone marrow radioprotection and reduction of WR-2721toxicityby Ocimum sanctum. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 1998;397(2):303-312. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Sood S, Narang D, Dinda AK, Maulik SK. Chronic oral administration of Ocimum sanctum Linn. augments cardiac endogenous antioxidants and prevents isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis in rats. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2010;57(1):127-133. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Kaul D, Shukla AR, Sikand K, Dhawan V. Effect of herbal polyphenols on atherogenic transcriptome. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;278(1-2):177-184. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Sarkar A, Lavania SC, Pandey DN, Pant MC. Changes in the blood lipid profile after administration ofOcimum sanctum (Tulsi) leaves in the normal albino rabbits. Indian J PhysiolPharmacol. 1994;38(4):311-312. PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Rehan HMS, Majumdar DK. Effect of Ocimum sanctum fixed oil on blood pressure, blood clotting time and pentobarbitone-induced sleeping time. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2001;78(2-3):139-143. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Othman GA, Ahmed DAEM, Alghamdi HA, Radwan AM. Antifungal activity of Syzygium aromaticum (Dianthus) against toxigenic Rhizopus stolonifera and its immunomodulatory effects in aflatoxin-fed mice. Trop J Pharm Res. 2019; 17(10):1991-1997. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Chattopadhyay RR, Sarkar SK, Ganguly S, Medda C, Basu TK. Hepatoprotective activity of O. sanctum leaf extract against paracetamol induced hepatic damage in rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 1992; 24(3):,163-165. Google Scholar Link

- Lahon K, Das S. Hepatoprotective Activity of Ocimum sanctum alcoholic leaf extract against paracetamol-induced liver damage in albino rats.Pharmacognosy Res. 2011; 3(1):13-18. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar

- Charitha V, J DA, Malakondaiah P. In Vitro Anthelmintic activity of Syzygium aromaticum and Melia Dubia against Haemonchus contortus of sheep. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2017; 87:968-970. Google Scholar Link

- Athanasiadou S, Kyriazakis I, Jackson F, Coop RL. Direct Anthelmintic effects of condensed tannins towards different gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep: In vitro and in vivo studies. Veterinary Parasitology. 2001;99(3):205-219. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Asha MK, Prashanth D, Murali B, Padmaja R, Amit A. Anthelmintic activity of essential oil of Ocimum sanctum and eugenol. Fitoterapia. 2001;72(6):669-670. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Kanojiya D, Shanker D, Sudan V, Jaiswal AK, Parashar R. Anthelmintic activity ofOcimum sanctumleaf extract against ovine gastrointestinal nematodes in India. Research in Veterinary Science. 2015; 99:165-170. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Raghavenra H, Diwakr BT, Lokesh BR, Naidu KA. Eugenol-The active principle from cloves inhibits 5-lipoxygenase activity and leukotriene-C4 in human PMNL cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;74(1):23-27. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Kozam G. The effect of eugenol on nerve transmission. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44(5):799-805. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Hosseini MM, Asl M, Rakhshandeh H. Analgesic effect of clove essential oil in mice. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2011:1(1):1-6. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Majumdar DK. Analgesic activity of Ocimum sanctum and its possible mechanism of action. International Journal of Pharmacognosy. 1995;33(3):188-192. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Galal A, Abdellatief S. Neuropharmacological studies on Syzygiumaromaticum (clove) essential oil. International Journal of Pharma Science. 2015; 5:1013-1018. Google Scholar Link

- Singh E, Sharma S, Dwivedi J, Sharma S. Diversified potentials of Ocimum sanctum Linn (Tulsi): An exhaustive survey. J Nat Prod Plant Resour. 2012,2(1):39-48. Google Scholar Link

- Sakina MR, Dandiya PC, Hamdard ME, Hameed A. Preliminary psychopharmacological evaluation of Ocimum sanctum eaf extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1990;28(2):143-150. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Samson J, Sheela Devi R, Ravindran R, Senthilvelan M. Biogenic amine changes in brain regions and attenuating action of Ocimum sanctum in noise exposure. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2006;83(1):67-75. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Ravindran R, Devi RS, Samson J, Senthilvelan M. Noise-stress-induced brain neurotransmitter changes and the effect of Ocimum sanctum (Linn) treatment in albino rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;98(4):354-360. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Feng J, Lipton JM. Eugenol: Antipyretic activity in rabbits. Neuropharmacology. 1987;26(12):1775-1778. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Taneja M, Majumdar DK. Biological activities of Ocimum sanctum L. Fixed Oil— an overview. Indian J Exp Biol. 2007; 45(5):403-412. PubMed Google Scholar

- Bouchentouf S, Said G, Noureddine M, Allali H, Bouchentouf A. A note study on antidiabetic effect of main molecules contained in clove using molecular modeling interactions with DPP-4 enzyme. International Journal of Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 2017;5:9-13. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Hussain EHMA, Jamil K, Rao M. Hypoglycaemic, hypolipidemic and antioxidant properties of tulsi(Ocimum sanctum Linn) on streptozotocin induced diabetes in rats. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2001;16(2):190-194. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Antora RA, Salleh RM. Antihyperglycemic effect of Ocimum plants: A short review. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2017;7(8):755-759. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Halder N, Joshi S, Gupta SK. Lens aldose reductase inhibiting potential of some indigenous plants.Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;86(1):113-116. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Issac A, Gopakumar G, Kuttan R, Maliakel B, Krishnakumar IM. Safety and anti-ulcerogenic activity of a novel polyphenol-rich extract of clove buds (Syzygiumaromaticum L). Food Funct. 2015;6(3):842-852. DOI PubMed Link

- Santin JR, Lemos M, Klein-Júnior LC, et al. Gastroprotective activity of essential oil of theSyzygiumaromaticum and its major component eugenol in different animal models. Naunyn-Schmied Arch Pharmacol. 2011;383(2):149-158. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Majumdar DK. Evaluation of the gastric antiulcer activity of fixed oil of Ocimum sanctum (Holy Basil). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1999;65(1):13-19. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Karmakar S, Choudhury M, Das AS, Maiti A, Majumdar S, Mitra C. Clove (SyzygiumaromaticumLinn)extract rich in eugenol and eugenol derivatives shows bone-preserving efficacy. Natural Product Research. 2012;26(6):500-509. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh S, Majumdar DK. Effect of fixed oil of Ocimum sanctum against experimentally induced arthritis and joint edema in laboratory animals.International Journal of Pharmacognosy. 1996;34(3):218-222. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Tao G, Irie Y, Li DJ, Keung WM. Eugenol and its structural analogs inhibit monoamine oxidase a and exhibit antidepressant-like activity. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;13(15):4777-4788. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Godhwani S, Godhwani JL, Was DS. Ocimum sanctum— A preliminary study evaluating its immunoregulatory profile in albino rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1988;24(2-3):193-198. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Taylor PW, Roberts SD. Cloveoil: An alternative anaesthetic for aquaculture. North American Journal of Aquaculture. 1999;61(2):150-155. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Diyaware MY, Suleiman SB, Akinwande AA, Aliyu M. Anesthetic Effectsof clove(Eugenia aromaticum) seed extract on Clariasgariepinus (Burchell, 1822)fingerlings under semi-arid conditions. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, Belgrade. 2017;62(4):411-421. DOI Google Scholar

- Pongprayoon U, Baeckström P, Jacobsson U, Lindström M, Bohlin L. Compounds inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis isolated from Ipomoea pes-caprae. Planta Med. 1991;57(06):515-518. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Hamackova J, Kouril J, Kozak P, Stupka Z. Cloveoil as an anaesthetic for different freshwater fish species.Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science. 2006; 12:185-194. Google Scholar

- Saeed SA, Gilani AH. Antithrombotic activity of clove oil. J Pak Med Assoc. 1994;44(5):112-5. PubMed Google Scholar

- Rasheed A, Laekeman G, Totté J, Vlietinck AJ, Herman AG. Eugenol and prostaglandin biosynthesis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(1):50-51. DOI PubMed Google Scholar

- Srivastava KC. Antiplatelet principles from a food spice clove(Syzgium aromaticum L). Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 1993;48(5):363-372. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Islamuddin M, Chouhan G, Want MY, Ozbak HA, Hemeg HA, Afrin F. Immunotherapeutic potential of eugenol emulsion in experimental visceral leishmaniasis.PLoSNegl Trop Dis. 2016;10(10):1-23.e0005011. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar Link

- Mukherjee R, Dash PK, Ram GC. Immunotherapeutic potential of Ocimum sanctum (L) in bovine subclinical mastitis. Research in Veterinary Science. 2005;79(1):37-43. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Bhakta S, Awal M, Das S. Herbal contraceptive effect of Abrus precatorius, Ricinus communis, and Syzygium aromaticumon anatomy of the testis of male Swiss albino mice. J Adv Biotechnol Exp Ther.2019;2(2):36-43. DOI Google Scholar

- Choi D, Roh HS, Kang DW, Lee JS. The potential regressive role of Syzygium aromaticumon the reproduction of male golden hamsters. Development &Reproduciton. 2014;18(1):57-64. DOI PubMed PMC Google Scholar

- Ahmed M, Ahamed RN, Aladakatti RH, Ghosesawar MG. Reversible anti-fertility effect of benzene extract of Ocimum sanctum leaves on sperm parameters and fructose content in rats. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. 2002; 13(1):51-59. DOI PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Kantak NM, Gogate MG. Effect of short term administration of tulsi (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) on reproductive behavior of adult male rats. Indian J PhysiolPharmacol.1992; 36(2):109-111. PubMed Google Scholar Link

- Singh V, Amdekar S, Verma O. Ocimum sanctum (tulsi): Bio-pharmacological activities. WebmedCentralPharmacology. 2010;1(10):1-7. DOI Google Scholar Link

- Joshi H, Parle M. Cholinergic basis of memory improving effect of Ocimum tenuiflorum Linn. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006; 68(3):364-365. DOI Google Scholar Link

Update History

| Revision Number | Date | Details Of Changes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2022-03-16 | Original Article; published at its accepted version (Reference Number: PPD/MIN/21111A) |

Pharmacotherapy & Pharmascience Discovery

Pharmacotherapy & Pharmascience Discovery

>> Click to Enlarge Table 2

>> Click to Enlarge Table 2

>> Click to Enlarge Table 4

>> Click to Enlarge Table 4 >> Click to Enlarge Table 5

>> Click to Enlarge Table 5 >> Click to Enlarge Table 6

>> Click to Enlarge Table 6